Epic Journey

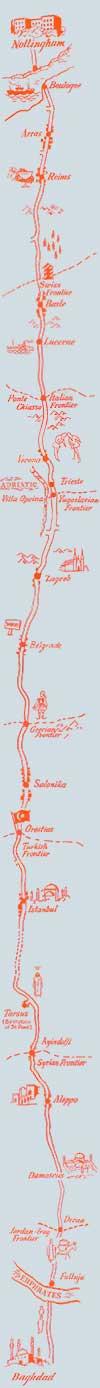

| How can you be in two places at the same time - especially when those two places are nearly 5,000 miles (8,000 km.) apart? The answer seems to be to travel between the two places by Armstrong Siddeley 'Sapphire'. That was, in exaggerated form, the problem that faced Mr. Geoffrey E. Macpherson, the managing director of the world-famous Nottingham textile and textile machinery firm of Geoffery E. Macpherson Ltd. The solution was certainly the one that was adopted. Mr. Macpherson is a dynamic man, full of drive and initiative. A born salesman, he believes that you do not sell your products by sitting in your office and waiting for customers to come to you but rather by taking them round for people to see. On this occasion his problem was that he had taken space at two exhibitions - one at Stockholm in Sweden and the other at Baghdad. The exhibitions were not actually open during the same period but it takes a long time to ship materials to Baghdad. The exhibits required they would have had to leave England before the show at Stockholm was even opened. Why, then, not have a duplicate set of exhibits and solve the difficulty easily that way? The answer is that these were of a costly and highly specialized nature, representing the latest advances in their field, that not only were two sets unavailable but that another one could not possibly have been prepared in time. Modern Merchant AdventurersMoreover, it would not have been a practical proposition to have the exhibits out of the country for such a long time. They consisted in the main of new yarns and equipment for testing yarn and cloth for strength, twist, and so on. Small difficulties of that kind do not easily perturb Mr. Macpherson. He took a quick decision to send them out to Stockholm in a caravan towed by his Armstrong Siddeley 'Sapphire' to bring them back to Nottingham for quick refurbishing after the exhibition had closed and then go by road all the way to Baghdad. Thus in the 20th century he was copying the ancient trading methods of the Middle East. The caravan would be useful not only to transport the equipment but also to provide facilities for preparing food, and for sleeping - not simply to solve the difficulty of finding good hotels without wasting time but because in many places hotels just did not exist. A member of his publicity department, Mr. R. H. Hodson, agreed to share the driving with him. The caravan of course, had to have certain normal fittings omitted since the equipment and exhibits that it was to carry weighed more than 1 1/2 tons (1,500 kg.). Loaded, it had an all-up weight of nearly 3 tons (3,050 kg.). Over Three Months SavedAnd the time saving? By normal transport a period of nearly four months had to be allowed for goods shipped from England to arrive in Baghdad. By road they got there in sixteen days. The journey itself from Stockholm to England was simplicity itself. As the roads were perfect and in many places there was no speed limit there were long stretches where 75 m.p.h. (120 km./h.) could be maintained with the 3-ton caravan on tow. On one occasion in Sweden they were stopped by the police who said that they were travelling at 100 m.p.h. (160 km./h.). Although the caravan was swaying a bit it was perfectly safe and they were allowed to proceed. The only set-back occurred in Holland when a spring on the caravan broke on a side road immediately outside a tiny garage where a new spring was built up in two hours for the very low cost of 30 florins (about £3). Lone JourneyBack at Nottingham the caravan was fitted with heavier wheels, tyres, and springs but the only modification to the standard 'Sapphire' (with 20,000 miles (32,000 km.) on the clock) was to fit special shock absorbers at the front. When this had been done everything was ready for the road to Baghdad. But not quite: for due to pressing business reasons Mr. Macpherson was unable to leave. So Mr. Hodson had to start out on the 4,800 mile (7,700 km.) journey alone, Mr. Macpherson promising to catch him up by air en route. There are few people who would set out on such a journey alone and towing a 3-ton caravan without trepidation. Only to read the R.A.C. itinerary is almost an adventure in itself. The route followed is shown roughly on this strip map. It crosses France, Switzerland, Italy, Yugoslavia, Greece and Turkey. From there it goes on through Syria and Jordan and into Iraq to the final destination, Baghdad. Over 500 miles (800 km.) of the journey are across desert and a great part of it over rough roads and ill defined tracks.  Grisly WarningsThe R.A.C. itinerary is hardly reassuring reading for the intending traveller. In it there are such warnings as: 'Approaching Belgrade the edges of the road are beginning to collapse and motoriists should beware of going too near them'. At Istanbul, on the other hand, there is a very prosaic instruction - 'Cross the Bosphorous by ferry running every hour or two in summer, but once a day at 8 a.m. at other times'. No mention at all of all the unwanted wives supposed to have ended their lives there in the past, dumped into the water in sewn-up sacks! For the section of the journey between Istanbul and Ankara the legend reads: 'This is the first stage of the road to the Far East, a road running across the vastness of Asia Minor, often becoming little more than a track over country possessing few hotels and none of the amenities of European touring'. Later, actual directions are missing, but the itinerary names various places and says: 'Enquire here for the road to so and so'. From Ankara to Adana is: 'A hill road over the heights of Turkey culminating in the famous Cilician Gates Pass, whence the road drops down to the coastal plains and Adana'. A glimpse of Eastern magnificence and biblical history is conjured up by the entry for the Cilician Gates Pass: 'Tarsus near here - birthplace of St. Paul and scene of the meeting of Cleopatra and Anthony when the latter sailed up the Cydnus in magnificent luxury. According to Mr. Hodson it all sounds very much more romantic than it actually was. He passes the whole outward trip off with a simple phrase: 'It was quite a comfortable journey'. But I believe that this is a masterpiece of understatement for it must have been hard going all the way with little or no time to stop and look at the scenery. For instance, the schedule allowed him only three days to pass through Yugoslavia, but the authorities provided a customs' officer as guide and without him the journey would never have been completed. Of roads there were none. Shearing Half-inch BoltsAll the way the 'Sapphire' ran beautifully but there was constant trouble with the towing bar for the caravan. Bolts measuring half-an-inch (1.3 cm.) in diameter by two inches (5 cm.) in length were continually being sheared. This slowed down progress considerably and beyond Italy there was also trouble with the petrol tank being pierced by stones and rocks thrown up from the roads.

The Hotel Splendid desert view A typical hotel in the desert - no wonder that Mr Macpherson decided to take a caravan on the journey. The last stage, over the desert, was, perhaps, a bit monotonous. The road stretched absolutley straight for 600 miles (1,000 km.) or so, and at the same time carried little traffic. When it was built, ten to fifteen years ago, it was an excellent highway but it has been greatly cut up by heavy vehicles during the years that have passed since then. Bumps abound. One car hit a bump and the driver lay disabled for 3 1/2 days before being found. Sometimes so much damage is done to a vehicle by such a bump that the only way to repair it is to wait until a complete new body can be shipped out from the country of manufacture.     As this is a motoring story there is limited space to tell of the adventures of Mr. Macpherson. He arranged a rendezvous in Istanbul with Mr. Hodson from where he was going to share the driving. They met according to schedule but things went wrong with passports and visis, involving many frantic excursions including the interruption of a congress of chief constables who could provide the required signature! When everything had been sorted out he chased the 'Sapphire" by private car, air and by Nairn's desert transport, continually asking: "Have you seen a 'Sapphire' towing a caravan?" He never quite caught up with it, always being told: "It passed through here a few hours ago". But eventually Baghdad was reached by them both.

At the fair the 'Sapphire' was the only car with a label permitting it to enter the grounds. This was signed by the Chief of Police of Iraq. Stuck on the windscreen the signature proved to be an 'open sesame' in many awkward situations, particularly as so many of the inhabitants were unable to read. When the two men left their hotel to visit the fair every day the police held up all other traffic for them to proceed, being quite certain that they were important British potentates not only because of the signature on the windscreen but also because they were driving an Armstrong Siddeley. The 'Sapphire' aroused great interest in both Baghdad and in most places throughout the journey. In Greece on one occasion the local police superintendent put a boy aboard to direct Mr. Hodson to a suitable parking place. All the way through the streets he was shouting to the populace "Follow me" and when they arrived the people crowded round the car so tightly that it was impossible to get out of it. Incidentally, the first day of the exhibition was rather a reverse of conditions at the S.B.A.C. show, since it was reserved exclusively for women visitors. All men, other than Europeans, were forbidden to enter. Homeward BoundThe return journey was different. It was arranged to drive to Beirut so that the car could be shipped to Marseilles to save the trouble with the towing bar, which was a particular nuisance on the very rough roads. One breakdown occurred in the middle of the desert and Mr. Macpherson managed to 'thumb' a lift on a passing bus which they had watched arriving for forty minutes. This drive was a nightmare. So straight was the road that the bus driver let the vehicle steer itself, holding the accelerator down with a stick while he put his feet up on the seat.

There was much difficulty in finding someone to make the repair to the towing bar that was necessary but, with the aid of the R.A.F., who put them in touch with a firm of contractors, the job was finally done and the bar did not break again. There is no space to tell all that happened during the incident. In the middle of the night Mr. Macpherson was taken by a friendly hotel keeper into his hotel and literally forced to have something to eat. He took Mr. Macpherson into the kitchen. When the light was lit Mr. Macpherson saw to his horror that the ceiling and all the walls and tables were absolutely covered with huge black-beetles. Fortunately, he spied a tin of sardines, realised that the beetles could not have been at them, and decided that he really wanted nothing better than a sardine! Fields Preferable To RoadsEventually, off they started again, only to loose the road and find welcome relief by driving for miles over ploughed fields. This provided better running than the normal road - in fact the best they had had for some time! Just as Beirut is reached there is a hill which rises from sea level to some 8,000 ft. (2,500 m.) in one straight climb, with a constant gradient of about 1 in 5. Right at the start of this the solenoid on the bottom gear in the electric gearbox went. As they carried a complete kit of spares the job could have been repaired but it was the middle of the night and therefore there was not enough light to do more than reverse the leads so that the top gear took the normal place of bottom. On descending the hill it was terribly difficult to keep the heavy caravan from over-running and the position of the electric gear change lever made things a bit complicated, for the driver had to remember that when this was in top the actual gearbox was in bottom. By this time both men were very tired. They had gone three days without sleep and with very little food for they had to reach Beirut in a limited time in order to catch a ship which was scheduled to leave at 6 o'clock in the evening, and thus avoid a long wait for the next one. 'It was the worst drive I have ever had', said Mr. Macpherson. 'One hundred degrees and more of heat, sand and more sand everywhere'. Beirut was reached at 10.00 p.m., four hours late - but the saling had been postponed until midnight. So they had the car washed and de-sanded and then left it locked up while they went to buy the tickets. The local garage, however, had penetrated the electric wiring with their hose pipes and when Mr. Macpherson and Mr. Hodson returned from the steamship office they had to fight their way through a big crowd which was interestedly watching the local fire brigade wrenching open the doors of the 'Sapphire' to put out a fire. All that really needed to be done was to lift the bonnet and unclip the battery leads. But this was too simple a solution! Nevertheless, the car was eventually put aboard the steamer and they sailed for Marseilles. "Altogether it was an interesting journey', said Mr. Macpherson to me, 'and the "Sapphire's" performance was really extraordinary. We had absolutely no difficulty with the car itself and but for the stupid work on the part of the Beirut garage we would have been O.K. We gave the car a very gruelling test indeed and had no mechanical and only one electrical difficulty, which was immediately resolved. It is remarkable that any car could go through such a hammering so successfully. 'The towing performance was extraordinary. We could and did do 65 to 75 m.p.h. (105 to 120 km./h.) down the Autobahn on the Continent with the caravan in tow - and, remember, it was not an ordinary caravan we were towing but one that weighed nearly 3 tons (3,050 kg.).' That speaks for itself. In Yugoslavia, however, Mr. Hodson was once able to cover only 170 miles (275 km.) in 24 hours owing to the shocking road conditions. These two set of figures provide an interesting comparison and show the diversity of the conditions experienced during the journey. Fast Run To Baghdad'I am so pleased with the performance of my "Sapphire" that, with two co-drivers, I would guarantee on any future occassion to reach Baghdad in four days after leaving the channel port'. The "Sapphire" is a magnificent car in every sense'. Could one say more?   G.D.S.G   |